Just found this in my Google documents. Written about 3 years ago. But, it means I can put some more pictures here.

—

Deleuze’s crystal-image purports to offer us an insight into the operation of time. In order to explore this claim I will provide a synopsis of Bergson’s though on time and memory, which informs Deleuze’s work concerning the crystal-image. The crystal-image is a logical culmination of a trajectory that Deleuze sees in cinema. This essay will deal with this trajectory that operates through the movement-image, time-image and into the crystal-image: the Second World War providing the paradigm shift in underlying cinematic style. Finally, and in order to determine how the crystal-image is delineated visually I will look at its portrayal in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo.

In each moment that we inhabit in the present there exists, for Bergson, a split between a present that passes, and a past which is preserved. Bergson’s description of time is derived from Xeno’s paradoxes of movement, and seeks to explain how we move through time. In order to make sense of this, Bergson ascribes to our subjectivities ‘duration’. “Pure duration is the form taken by the succession of our inner states of consciousness when our self lets itself live, when it abstains from establishing a separation between the present state and anterior states.”1 This notion of duration provides the basis of Bergson’s work on memory and features in Deleuze’s analysis of the crystal-image; itself a portrait of duration, a depiction of “the foundation of time, non-chronological time”.2 It is only through looking at Bergson’s work on memory that we can fully make sense of duration (and thus the crystal-image); though it is itself, a concept that superintends the memory schema.

In order to explain how the past survives in the present, and how the splitting of time is facilitated, Bergson divides the operation of memory into two distinct aspects. The two forms that memory takes are of spontaneous memory and habitual or automatic memory. Spontaneous memory deals with the past in images and representations; it is entirely virtual.3 Habitual memory, unlike spontaneous memory, engages with the present. In elaborating on Bergson’s work, Guerlac uses the example of driving a car and then failing to acutely remember the journey afterwards.4 The mechanism of habitual memory, through the learned skill of driving, engages with the present. The practical collaboration of the two types of memory can be referred to as actual memory and is necessarily expedient in dealing with the world.

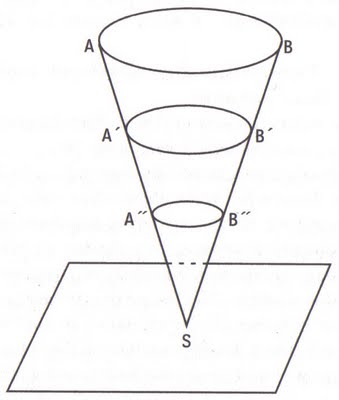

Bergson illustrated this interaction between spontaneous and habitual memory, and perception through his inverted cone. What we see is a distinction between the virtual – that which is pure memory, and the actual – pure perception, involved with the present. This gap is bridged through the use of memory. The ellipse AB at the base of the cone is totality of memory. Point S is the body, the self, in contact with the present (shown as the plane P). What needs to be considered is that the diagram is not meant to convey stasis; point S is in constant motion, engaged in a perpetual surge towards an immediate future and linked with an immediate past. This is how time is experienced, through the mechanism of memory Bergson describes. Time is not linear, but amorphous and in flux. The past exists concurrently with the present and each point in the future splits into a present that passes and a past that is preserved, without this there could be no motion through time: time would not move if the present could not pass.

Deleuze suggests that Bergson’s philosophy has often, pejoratively, been reduced to the maxim that “duration is subjective and constitutes our internal life.”5 While there is no denying the truth of the statement it can only be made sense of in the wider context of Bergson’s philosophy. Through the schema of time and memory that Bergson outlines it is the constant production of ‘internal circuits’, the linking of present and past, which contribute to the subjectivity of duration. It is these internal circuits that Deleuze finds exemplified visually through the medium of cinema.

Deleuze argues that these internal circuits when delineated in cinema give us a picture of how we inhabit and move in time. 6 It is this that he terms the ‘crystal-image’ – a representation of the splitting of time, the movement of past and present reflected through these images. Deleuze states that “cinema does not just present images, it surrounds them with a world.”7 He goes on to elaborate that cinema seeks to provide bigger circuits in order to link actual images with those of the past. This is the basis for what Deleuze sees as the cinema’s exposition of time. However, the purest form of the crystal-image, the manner in which we exist in time, constitutes the smallest possible internal circuit.8 What Deleuze seeks to provide is a taxonomy of the crystal-image. To look at the crystal-image in film we require its context in Deleuze’s cinematic trajectory.

For Deleuze the state of pre-war cinema is characterised by a portrayal of the movement-image. The movement-image arises from Bergson’s critique of cinema. Cinema “misconceives movement” in the same manner as natural perception. What it does is break down movement into a series of successive images, a misgiving that natural perception and cinema share.9 For Bergson a model in which things “constantly change, a flowing-matter in which no point of anchorage nor centre of reference would be assignable” would be preferable.10 It is this that leads to a plane of immanence, a universe, which is comprised in a set of movement images; everything reacts with everything.11 It is this that Deleuze adopts as the basis of the movement-image.

The movement-image is fundamentally reactionary. Its archetype is in Hollywood genre cinema, built upon placing characters into situations in which they can immediately act and react.12 Deleuze also states that the narrative of pre-war film, steeped in movement-image, carries little central to the main tenets of the plot. The construction of films is done with ease of accessibility firmly in mind. Cuts are made in order to advance in time towards the next stage of the story, which inevitably unfolds in a linear fashion, often signposted by elucidating flashbacks. It carries a sensory-motor schema through which action unfolds.13 The link between sense and motor, between perception and action, is unassailable. This is the basis of the movement image, the emphasis being firmly on spatial rather than temporal action.

The break with movement-image cinema originates in post-war cinema. The time-image is introduced. A method in which film-makers no longer sought to portray only the movement-image, a format that Deleuze asserts, exhausted itself of original content. It must be noted that the validity of Deleuze’s assertion – that the Second World War signalled a break in the ethos of filmmakers – is questionable. It is difficult to see just how a historical event (regardless of its size) could produce identical outcomes in a diffuse set of filmmakers spread globally. We are inclined to think of the time-image as born fully developed. This, perhaps, is a misconception. The Second World War can be said to have provided the catalyst for the development of the time-image, but this itself was a process that developed gradually: through the French new-wave, and the importation of an aesthetic from Japanese cinema. Post-war cinema did not suddenly lose its emphasis that had traditionally been placed on the movement-image, but embraced a blossoming new direction concerned with time over movement.

What the developed time-image does it to place characters in situations to which they are unable to react. The sensory-motor schema is dissolved, and prompt action and reaction consequently rendered unfeasible. Deleuze terms this type of image the opsign, and through it we gain cinematic glimpses of time in its pure state. Deleuze credits Ozu’s languorous style with the first major depictions of time in its purest essence. He notes that places devoid of people, lingering camera shots (prominently for Deleuze, of a vase in Late Spring) convey pure time.14 With time cinematically delineated, it is the work of the crystal-image to show us how we inhabit and operate within time.

Crystal-images, formed by the collision of the actual and virtual, allow us to see time. The limpid, actual image and the opaque, virtual, become accessible in the crystalline form.15 What constitutes the purest crystal image is when the “actual optical image crystallizes with its own virtual image”.16 This image that consists of the smallest internal circuit, where the actual image finds its own ‘genetic’ element, forms a pure crystal. The image becomes irreducible to the actual and virtual, the present and contemporaneous past. The image cannot be broken down into its constituent parts because they become indiscernible from each other. Deleuze even suggests that in the light of the actual, the virtual becomes the actual and the actual, virtual, in the crystal.17 There is fluidity in the crystal that means its parts cannot be demarcated.

The crystal-image is the present and past, co-existing. Bergson holds that this is evinced in the form of déjà-vu.18 The phenomena of finding a place familiar, of feeling as if we have been somewhere or done something before, is the simultaneous existence of the past and present: where the pure-virtual image interacts fleetingly with present. This virtual image, in its pure form, exists outside of the consciousness in time. In the crystal-image, in déjà-vu, we glimpse this vision of an anterior state in collaboration with the present. This, is for Deleuze, how we operate in time, time holds us in its interior and we move through it as such.19

There are only three films that Deleuze attributes with showing us how we move in time; of forming crystal-images composed of the smallest interior circuits: Dovzhenko’s Zvenigora, Resnais’s Je t’aime je t’aime and Hitchcock’s Vertigo.20 It is telling that there are only three examples of the crystal-image for Deleuze. It is an image of unrivalled specificity whose potential we can see in many films, but whose existence is only available to us in few. The theory of the crystal-image and the intricacy of its composition, often lead to situations where a lacuna is required to complete the crystal. This means that although the theoretical apparatus of the crystal-image can be applied to many films, we can rarely use it as an explanatory tool. Indeed, for Deleuze, it is not the crystal-image that can be used to further our understanding of specific films, but that these films further our understanding of the fundamental metaphysics of time and memory.

In Resnais’ Hiroshima, Mon Amour, in the Casablanca bar, the memories of Elle are projected onto Lui, so that in conversation he becomes her German lover. The crystal though is not quite completed, as it lacks the synchronous unity of a moment shared through past and present. Similarly, Lynch often offers us images of a virtual past imposed upon the present (think of line “Dick Laurent is dead” in Lost Highway) that leads to an exploration of a fugue state with continual references to events both present and past. What Deleuze does not allow for in the crystal-image is the construction of an implicit state of reference that has the same temporal significance. What the crystal-image requires is an explicit exposition; a full visual representation of the workings of memory in time. It is for this reason that I shall focus exclusively on the portrayal of Deleuze’s crystal-image in Hitchcock’s Vertigo.

Chris Marker puts forward the idea that Scottie’s acrophobia in Vertigo is a “clear, understandable and spectacular” metaphor for the vertigo of time.21 What Scottie tries to overcome through his makeover of Judy into Madeleine is time itself. His obsession, born from his love for Madeleine realises itself in his project to makeover a small town Kansas girl into the lady he covets. It is this fight against time that Vertigo portrays. It shows how Scottie inhabits time, and the function of his memory in his interaction with the present.

Vertigo is constructed in a manner that betrays its ostensible fascination with spatial vertigo. Vertigo contains multiple instances of repetition, semiotics, mirror images and duplicitous appearances. Dialogue is repeated, most notably the line about ‘power and freedom’, first uttered by Elster as a lament for a San Francisco past. These are the concepts that underline Elster’s machinations. What we are witness to is an elaborate plot to rid himself of his wife, thus gaining freedom, retaining her money as a key to power. In the Argosy bookstore the line is repeated alongside the rather portentous statement from Pop Leibel (‘he threw her away’) about Carlotta Valdes. Something that Elster manages to do literally, discarding his wife from the bell tower while Judy stands complicit.

The spiral of the opening credits, Madeleine’s hair and the stairs of the bell tower symbolise the circular nature of time in Vertigo. Things are brought back to approach their origins but the circuits can never quite be completed: the death of Madeleine prevents the logical culmination of the love she shares with Scottie, a situation that repeats itself with Judy’s death in the finale of the film. All symbols for Deleuze, of the operation of time. Indeed the prevalence of ‘mirror’ shots and the duplicitous nature of Madeleine further blur the distinction between the actual and the virtual. A technique used in the construction of the film as a whole. The ending mirrors the start, Scottie hanging once literally and then metaphorically in grave danger, the first physical and the second psychological. The pattern of following Madeleine and her death mirrors that which occurs, in the second half of the film, with Judy.

As Bergson saw, time is often viewed as secondary in function to space: in noting that we count in space, not time; that each object requires juxtaposition with another to make sense of them numerically.22 It is this reversal that constitutes metaphor of acrophobia that Marker uncovers in Vertigo. Indeed Deleuze states that the crystal-image “does not abstract time; it does better: it reverses its subordination in relation to movement”.23 This is what Scottie is seeking in making over Judy, to reverse this spatiotemporal hierarchy in order to recover what has been lost; Madeleine, but survives outside of his consciousness in time, in the realm of the virtual. The pure crystal-image – where the actual: the reshaping of Judy into Madeleine, meets the virtual: Scottie’s memory of Madeleine – is the zenith of time’s representation in Vertigo.

The pure crystal-image, where the actual meets its virtual image occurs in Vertigo, after Scottie has successfully remade Judy into Madeleine. In Judy’s room at the Empire Hotel, as her hair is twisted into Madeleine’s spiral, the transformation is completed. What follows is a kiss between Judy and Scottie. As they embrace in the room the camera begins to rotate around them, Scottie opens his eyes and the scenery changes. He is no longer in the Empire Hotel, but in the livery stables at the mission, with the memory of the kiss he shared with Madeleine before her perceived death. As the camera completes its circuit Scottie is returned to the hotel room.

It is this image, this pure crystal, which portrays time so effectively for Deleuze. What we are presented with is an irreducible image. The actual (the room in the Empire Hotel) and the virtual (the kiss in the livery stable) cannot be separated; there is no longer a distinction between the present and the past for Scottie at that moment. The virtual image becomes actual and limpid, while the actual becomes opaque.24 This is evinced in Vertigo. As the camera rotates, the virtual is shown to us; Scottie’s memory becomes actual, while the present, the actuality of the hotel room, disappears into the realm of the virtual. What we see in the crystal-image is the “gushing forth of time”. 25

It is through Scottie’s obsession and “thanks to the most magical camera movement in the history of cinema” that Vertigo portrays the crystal-image.26 This image is a product of Deleuze’s wider philosophy and a belief that through art we are able to reconcile ourselves with an alienated world: to come to terms with our position within it, and attempt to understand it more fully. In film – through the crystal-image – we are able to see the “most fundamental operation of time”.27 In Vertigo, we are shown time’s operation, how Scottie is positioned in time, and thus, how we inhabit time.

Bibliography

Barr, Charles, 2002, Vertigo, British Film Institute.

Bergson, Henri, 2001. Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Data of Immediate Consciousness. (Pogson Translation) Dover Publications.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1986 (first published 1983), Cinema One: The Movement-Image, Continuum Books.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books.

Guerlac, Suzanne, 2006. Thinking In Time – An Introduction To Henri Bergson. Cornell University Press.

Marker, Chris, 1995 ‘A free replay (notes on Vertigo)’in John Boorman and Walter Donohoe (ed) Projections 4 ½, Faber and Faber Ltd.

Pearson, Keith Ansell, 2002. Philosophy and the Adventure of the Virtual. Routledge.

Filmography

Hiroshima Mon Amour. Resnais, Alain. 1959 Argos Films.

Lost Highway. Lynch, David. 1996. Asymmetrical Productions.

Sans Soleil. Marker, Chris. 1983. Argos Films.

Tokyo Story. Ozu, Yasujiro. 1953. Artificial Eye Film Company Ltd.

Vertigo. Hitchcock, Alfred. 1958. Universal.

1 Bergson, Henri, 2001. Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Data of Immediate Consciousness. (Pogson Translation) Dover Publications. P. 100.

2 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 79.

3 Guerlac, Suzanne, 2006. Thinking In Time – An Introduction To Henri Bergson. Cornell University Press. P. 125.

4 Guerlac, Suzanne, 2006. Thinking In Time – An Introduction To Henri Bergson. Cornell University Press. P. 126.

5 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 80.

6 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 80.

7 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 66.

8 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 68.

9 Deleuze, Gilles. 1986 (first published 1983), Cinema One: The Movement-Image, Continuum Books. P. 59.

10 Deleuze, Gilles. 1986 (first published 1983), Cinema One: The Movement-Image, Continuum Books. P. 60.

11 Deleuze, Gilles. 1986 (first published 1983), Cinema One: The Movement-Image, Continuum Books. Pp. 61-63.

12 Deleuze, Gilles. 1986 (first published 1983), Cinema One: The Movement-Image, Continuum Books. Pp. 145-154.

13 Deleuze, Gilles. 1986 (first published 1983), Cinema One: The Movement-Image, Continuum Books. Pp. 159-163.

14 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. Pp. 13-16.

15 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 69.

16 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 67.

17 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 68.

18 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 77.

19 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 80.

20 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 80.

21 Marker, Chris, 1995 ‘A free replay (notes on Vertigo)’in John Boorman and Walter Donohoe (ed) Projections 4 ½, Faber and Faber Ltd. P123.

22 Guerlac, Suzanne, 2006. Thinking In Time – An Introduction To Henri Bergson. Cornell University Press. Pp. 61-63.

23 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 95.

24 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 68.

25 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. P. 80.

26 Marker, Chris, 1995 ‘A free replay (notes on Vertigo)’in John Boorman and Walter Donohoe (ed) Projections 4 ½, Faber and Faber Ltd. P. 124.

27 Deleuze, Gilles. 1989 (first published 1985), Cinema Two: The Time-Image, Continuum Books. Pp. 78-79.

—

It’s all in the spiral.

May 26, 2010 at 9:48 pm

[…] the crystal-image, in an earlier post on Cinema II and Tarkovsky, as follows: Deleuze’s crystal-image is a moment that simultaneously looks forward to the not-yet and back to a past that set the […]

May 26, 2010 at 9:55 pm

[…] the crystal-image, in an earlier post on Cinema II and Tarkovsky, as follows: Deleuze’s crystal-image is a moment that simultaneously looks forward to the not-yet and back to a past that set the […]

October 11, 2011 at 9:30 pm

Brilliant work. Definitely helped me understand Cinema 2 better.

March 1, 2014 at 11:42 am

so very helpful. who is to be given credit for this text? i could not find the blogger’s name.

March 3, 2014 at 10:03 am

Radia, allfordeadtime [at] gmail.com if you want details.